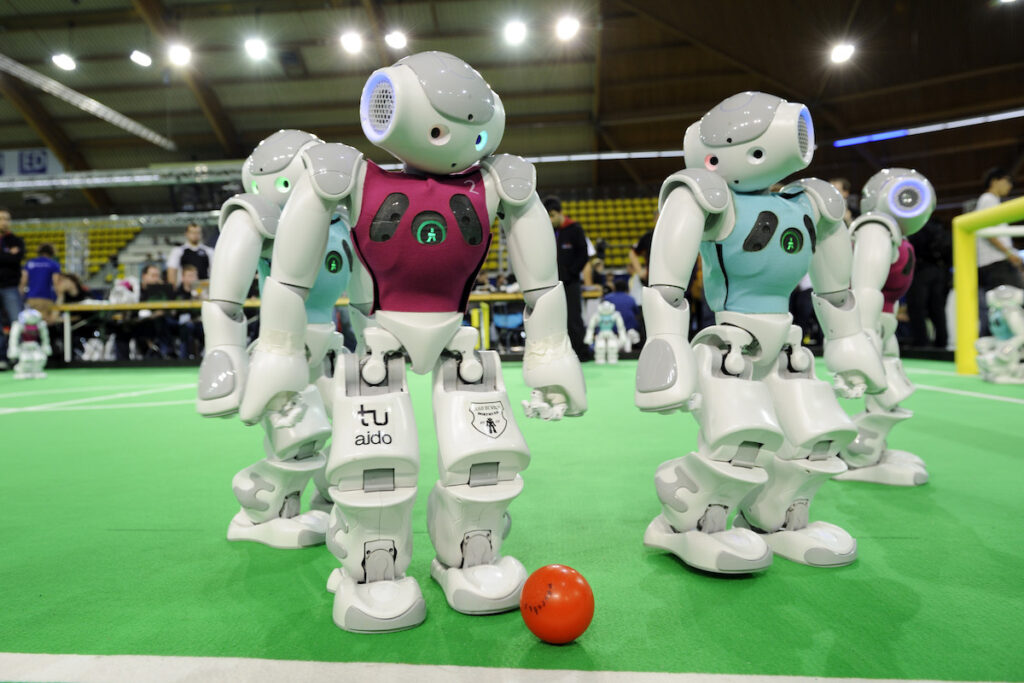

If you think a robot will steal your job, you are not alone. Soccer players should be worried too. The next Messi probably won’t be of flesh and blood but plastic and metal.

Becoming a fan of a team playing in the big leagues of smart machines is now a reality. Regional and international competitions are held regularly —and we don’t have to wait four years to enjoy the robots world championship— the RoboCup is held every year.

The concept emerged during the conference “Workshop on grand challenges in artificial intelligence,” held in Tokyo in 1992, where researchers discussed using robotic soccer players to boost investigations on humanoid machines. Independently, in 1993, Professor Alan Mackworth from the University of Bristol in Canada described an experiment with small soccer players in a scientific article, published in Computer Vision: Systems, Theory, and Applications. He pointed out that “A long term goal is to have teams of robots engaged in cooperative and competitive behaviour.”

Over 40 teams already participated in the first competition in 1997.

Soccer games driving research

The idea behind artificially intelligent players is to investigate how robots perceive motion and communicate with each other. Physical abilities like walking, running, and kicking the ball while maintaining balance are crucial to improving robots for other tasks like rescue, home, industry, and education.

Results of these applications were already harvested during the 9/11 events, where a team of RoboCup rescuers participated in trying to save people from the collapsing World Trade Center.

The big leagues of smart machines

Designing robots for sports requires much more than experts in state-of-the-art technology. Humans and machines do not share the same skills. Engineers need to impose limitations on soccer robots to imitate soccer players as much as possible and ensure following the game’s rules.

The restrictions on players’ design and rules of the game are imposed by the RoboCup Soccer Federation, the “FIFA” of robots.

The RoboCup Soccer Federation supports five leagues. Each has its own robot design and game rules to give room for different scientific goals. The number of players, their size, the ball type, and the field dimensions are different for each league.

In the humanoid league —yes, you guessed it— the players are human-like robots with human-like senses. However, they are rather slow. Many of the skills needed to fully recreate actual soccer player movements are still in the early stages of research.

The game becomes exciting for middle and small size leagues. The models are much simpler; they are just boxes with a cyclopean eye. Their design focuses on team behavior: recognizing an opponent, cooperating with team members, receiving and giving a standard FIFA size ball.

Soccer robots’ intellectual and physical abilities

For us, humans, every movement and use of our senses seem trivial. For robots, everything is a challenge, for example, recognizing the floor from the walls or a robot mate from a human being.

Today, soccer robots are entirely autonomous. They wireless “talk” to each other, make decisions regarding strategy in real-time, replace an “injured” player, and shoot goals. The only person in a RoboCup game is the referee. The team coaches are engineers in charge of training the RoboCups’ artificial intelligence for fair play: the robots don’t smash against each other or pull their shirts.

If your soccer team is not doing well, consider becoming a fan of a robot’s soccer team. Probably they won’t disappoint you. For example, the Tech United team from TU Eindhoven in the Netherlands is already a four-time world champion.

The next RoboCup competition will be played on June 22, 2021, virtually, with rules that will allow teams to participate without establishing physical contact.

The RoboCup Federation’s ambition is not shy; they want to play and win a game against a real-world cup human’s team by 2050.

References

- A. K. Mackworth, (1992). On Seeing Robots. Computer Vision: Systems, Theory, and Applications.

- A. Basu and X. Li, Eds. (1993). World Scientific. Press, Singapore. Presented at Vision Interface 92. VI-92, Vancouver, BC, May 1992.

Video: RoboCup 2019 – Middle size League. Finals Recap – Tech United from Eindhoven (orange) vs Water from Beijing (blue).

Illustrations by Smriti Srivastava.