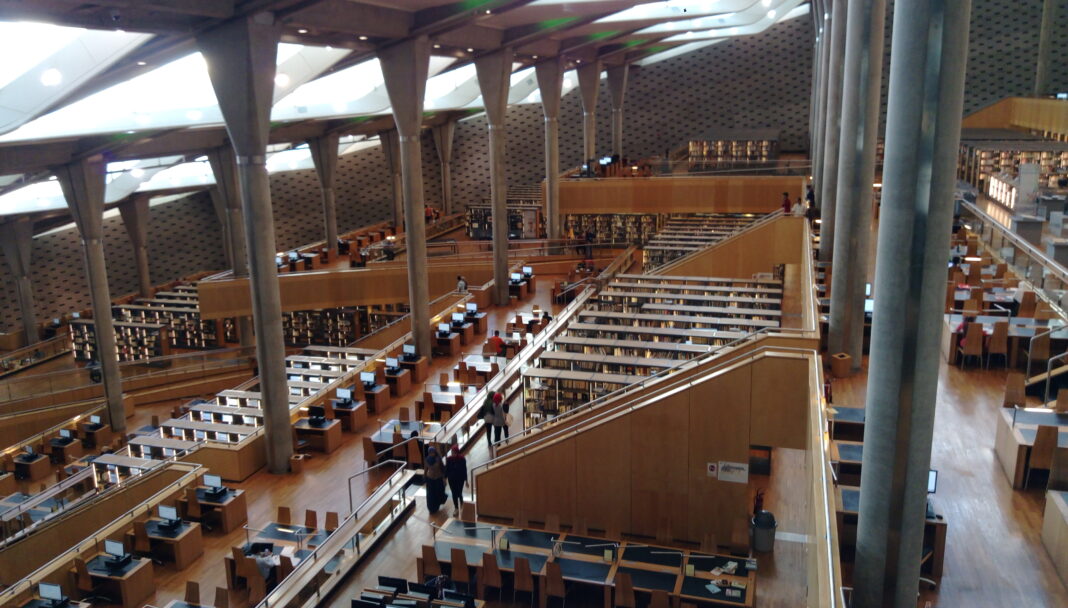

Knowledge sharing: from Alexandria’s Library to Open Access.

[su_dailymotion url=”http://www.dailymotion.com/video/x3c5wln_cosmos-a-spacetime-odyssey-hd-episode-13-unafraid-of-the-dark_school#tab_embed” quality=”240″ related=”no”]

History has told us that blood spilling is the most common result of a rivalry between ancient cultures. But Alexandria’s Library is an exception to this rule: knowledge blossomed from competition and the greatest library in the world was born (blood was also involved, though).

Around the year 300 BC, Demetrius of Phalerum was appointed by the Macedonian king to govern Athens. After a successful period ruling Athens, Demetrius had to escape to the court of Ptolemy I, in Alexandria. There, he convinced Ptolemy I to build the ‘Musaeum’ – the modern word ‘museum’ derives from this period – the first piece of the Alexandria’s Library complex puzzle. Demetrius dreamt of a library that contained a copy of every book in the world: a library that could compete with the rivals in Athens.

A copy of every book in the world

The Museum was a religious institution, a tribute to the Muses, the Greek goddesses of artistic and intellectual pursuit. But the Museum was, above all, a place for cultural sharing, with lecture areas, laboratories, botanical gardens, a zoo and, of course, the library itself. Alexandria’s Library soon outcompeted Athens’ schools, with famous thinkers such as Euclid, Archimedes, Herophilus, [su_lightbox src=”https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=nRkReKGFqHY”]Hypatia[/su_lightbox], and Aristarchus of Samos. The Alexandria’s Library sponsored scholarly activity, rather than sponsoring individuals, as happened in Athens’ schools. In theory, its intellectual legacy would last far longer than that of the Greek empire, it would travel for generations to come.

The Ptolemy clan’s hunger for knowledge was well-known. They were determined to have a copy of every book in the world. Buying books in Athens’ markets was one way of increasing their collection, but they went further, by dictating that all ships arriving at Alexandria’s harbors must be inspected. Every book found was taken away and copied. Alexandria’s Library would keep the originals and return the copies to its previous owners. The Library’s magnitude was unprecedented. Legend has it that more than half a million documents, mainly papyrus scrolls, were stored in its walls.

The fall of a symbol

Nowadays, the Library of Alexandria is perhaps best known as a symbol of knowledge destruction than a symbol of knowledge itself. What exactly happened and who was responsible for it is still a mystery, even though it is commonly believed that the library was burned. Several authors account Julius Caesar responsible for the tragedy. In 48 BC, during Alexandria’s occupation, he had one of his men set fire to Egyptian boats, but it is believed that the fire eventually got out of control and spread to the library’s warehouse.

Records show that the Library still existed after Caeser’s invasion, so he was not the only one responsible for the Library’s destruction. When paganism was made illegal, in 391, Theophilus of Alexandria decreed that a Christian church should be built on the site of one of the Library’s former buildings. Later, in 642, the Arabian army, led by Amr ibn al `Aas, captured Alexandria. The story goes that, when asked what to do with the library, Amr replied that “either the books contradict the Koran, in which case they are heresy, or they agree with it, in which case they are unnecessary”.

In an age where knowledge is one click away, one screen afar, the importance of the Library of Alexandria, and its subsequent destruction, is perhaps hard to grasp. But the very concept of knowledge sharing is one that is not strange to United Academics. Hundreds of years later, we don’t need to search for books in ships; open access will do the job.

Sources:

Erskine, A. (2009). Culture and Power in Ptolemaic Egypt: the Museum and Library of Alexandria Greece and Rome, 42 (01), 38-48 DOI: 10.1017/S0017383500025213

Brian Haughton. “What happened to the Great Library at Alexandria?,” Ancient History Encyclopedia. Last modified February 01, 2011. http://www.ancient.eu /article/207/

Cosmos: A Spacetime Odyssey HD | Episode 13 : Unafraid of the Dark