Impressionism, the popular art style that emerged in the 19th century, is often celebrated for its vibrant colors and ethereal quality. However, a new study suggests that there is more to these paintings than meets the eye. According to research published in PLOS, Impressionism contains elements of polluted realism. In the 19th century, air pollution reached unprecedented levels due to the Industrial Revolution. Even though direct measurements from this time period are scarce, paintings from this era could document longer-term environmental change. The study conducted by a team of scientists from the United States and Europe shows that artists such as Turner and Monet documented changes in atmospheric pollution in London and Paris through their paintings, providing a unique window into historical trends in air quality.

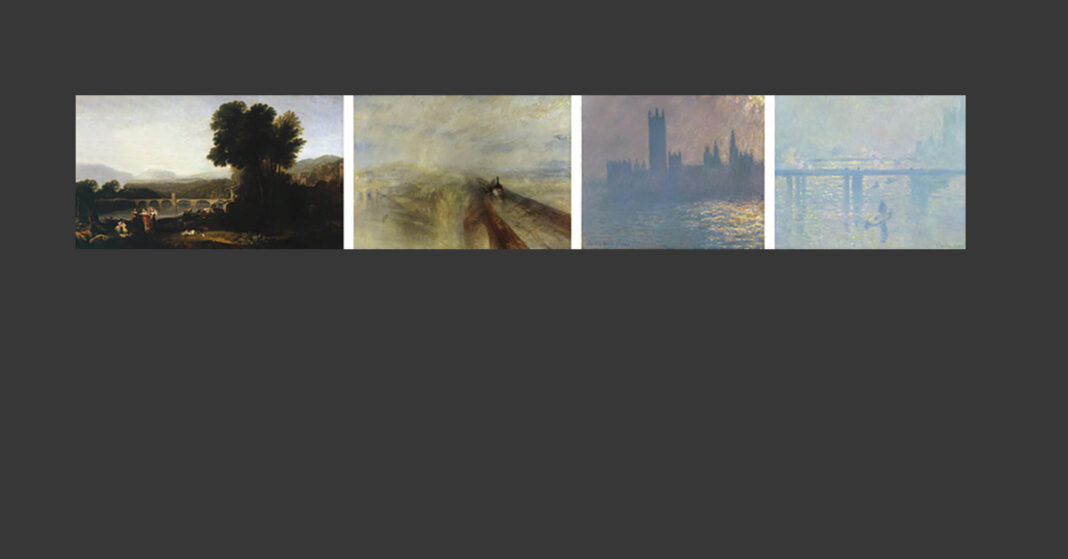

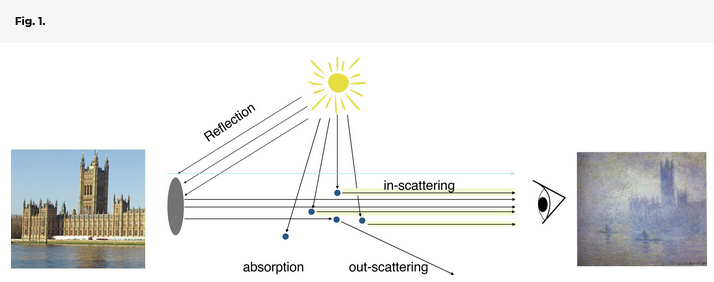

The article demonstrates that the progression toward hazier contours and whiter color palettes in Turner and Monet’s paintings and other artists is consistent with the optical changes expected from higher atmospheric aerosol concentrations. Monet and Turner’s stylistic changes from more figurative to impressionistic suggested that their works could capture elements of the atmospheric environmental transformation during the Industrial Revolution.

The study used a mixed-effects model to analyze the paintings, which allowed the researchers to account for both temporal and environmental trends. The model showed a significant dependence on emissions of sulfur dioxide -SO2 emissions-, indicating that atmospheric pollution contributed to depicting the contrast in Turner and Monet’s paintings. The researchers note that while there are limitations to using paintings as a proxy for historical air quality, the evidence provided is complementary to instrumental measurements.

Painting pollution

Anthropogenic aerosol emissions increased dramatically during the 19th century due to industrialization, particularly in Western European cities. Researchers investigate whether changes in atmospheric conditions were reflected in changes in painting style. They focused on Turner and Monet, who frequently painted landscapes and cityscapes during the Industrial Revolution. The team analyzed the contrast between 60 oil paintings by Turner and 38 paintings by Monet.

They found that Turner and Monet’s paintings underwent a visual progression from sharp to hazier contours, more saturated to pastel-like coloration, and figurative to impressionistic representation. Accordingly, a mixed-effects model showed that local SO2 emissions were a highly significant explanatory variable for the observed trends in contrast and intensity across the artists’ works. The findings suggest that both painters captured changes in the optical environment associated with increasingly polluted atmospheres during the Industrial Revolution.

Even when industrialization changed the environmental context in which painting occurred, the degree of decreased contrast and increased intensity representing physical, and optical changes associated with a polluted atmosphere is uncertain. Even so, the team proposed two further considerations about environmental trends rendered in the works of Turner and Monet.

On one hand, the environment depicted in their paintings was subject to large trends in atmospheric pollution. On the other, Turner and Monet likely intended to represent environmental change. Turner spoke about finding artistic material in his environment, while Monet’s serial views of London’s House of Parliament, Waterloo Bridge, and Charing Cross Bridge indicate a deliberate effort to capture the changing environment.

The study also brought to light some letters where Monet wrote about the role of air pollution in his creative process, “What I like most of all in London is the fog”. This makes it possible to infer that he did not choose the scenes to paint randomly. According to earlier investigations, there is some evidence that Monet chose to paint on days when ambient air pollution would have been higher on account of meteorological conditions.

Artistic work and environmental conditions

Overall, researchers pointed out that the new atmospheric conditions revealed in the paintings of Turner and Monet could inform environmental research, providing insights into the state of the atmosphere before the advent of widespread, direct measurements. Furthermore, this work demonstrates the potential of artistic works to provide a unique perspective on historical environmental change.

Researchers also highlight that the analysis has implications beyond the art world. With megacities such as Beijing and New Delhi experiencing levels of air pollution similar to those of 19th-century London, this approach drives attention to the impact that environmental change can have on how we see the world.

Moreover, they indicate that the evidence about Turner, Monet, and others depicting physical atmospheric conditions provides additional, complementary opportunities for appreciating and interpreting their artwork. “Our view is that impressionistic paintings recording natural phenomena—as opposed to being imagined, amalgamated, or abstracted—does not diminish their significance; rather, it highlights the connection between environment and art”, researchers pointed out.

References

Albright, A. L., & Huybers, P. (2023). Paintings by Turner and Monet depict trends in 19th-century air pollution. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences of the United States of America, 120(6). https://doi.org/10.1073/pnas.2219118120

Brimblecombe, P. (1977b). London air pollution, 1500–1900. Atmospheric Environment, 11(12), 1157–1162. https://doi.org/10.1016/0004-6981(77)90091-9

Corton, C. L. (2015). London Fog: The Biography. Harvard University Press.

Mage, D. T., Ozolins, G., Peterson, P. A., Webster, A. K., Orthofer, R., Vandeweerd, V., & Gwynne, M. D. (1996). Urban air pollution in megacities of the world. Atmospheric Environment, 30(5), 681–686. https://doi.org/10.1016/1352-2310(95)00219-7

Shaw, W. N. (1901). The London Fog Inquiry. Nature, 64(1670), 649–650. https://doi.org/10.1038/064649b0

The pictures showcase in the article belong to the paper: Albright, A. L., & Huybers, P. (2023). Paintings by Turner and Monet depict trends in 19th-century air pollution. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences of the United States of America, 120(6)