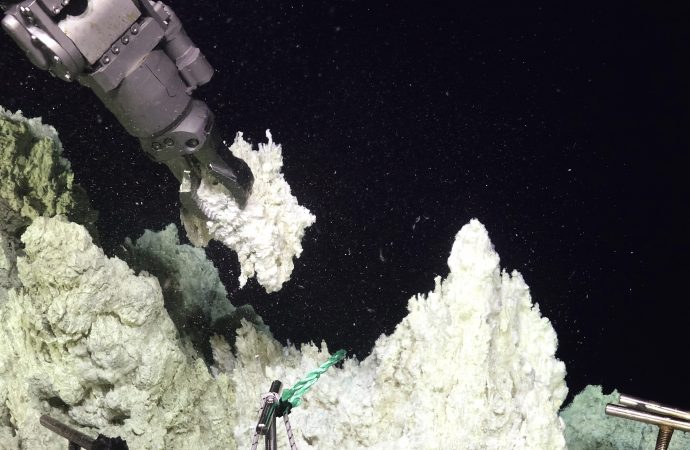

The majestic white spires of the Lost City protrude out of a mountain located 800 meters below the Atlantic Ocean. In December of 2000, a team of researchers set out aboard the research vessel Atlantis to explore why a large undersea mountain formed along the Mid-Atlantic Ridge. They serendipitously stumbled upon the spires and named the site “The Lost City”.

A few million years ago, at this site, a geological process exposed rock from Earth’s mantle to the ocean. As these rocks emerged to form the mountain the Lost City sits upon, rock-water reactions known as serpentinization began forming the towering chimneys.

A Special Kind of Chimney

The Lost City chimneys are unique. Almost all other hydrothermal systems on the seafloor are created by the movements of magma underneath the oceans. The resulting iconic ‘black smoker’ chimneys are essentially volcanoes, emitting huge clouds of billowing black smoke full of minerals like iron sulfides. They are covered in a rich community of red and white tube worms, clams, shrimp, and other diverse life reliant on the minerals ejected from the center of the Earth.

In contrast, the Lost City chimneys vent clear fluids. At first glance, they seem barren of life. But zoom in closer, and attached to rocks you’ll see thick layers of snotty-like fibers resembling white algae dancing around in the seawater. These gunky communities, called biofilms, are the most abundant life in this ecosystem. These single-celled micro-organisms are just as reliant on the venting fluids as the macro-organisms in the black smoker vents.

The venting fluid from Lost City chimneys is warm, clear, and full of hydrogen and methane. Chimneys reach a maximum temperature of 100°C, and the fluids are alkaline with a pH around 10. The black smokers, in comparison, can reach an impressive 400°C and have a more acidic pH ranging from 2 to 5. These differences are caused by the different types of rocks below the two types of chimneys. The chemical composition of the mantle rocks underneath the Lost City is the reason why the serpentinization reactions can produce hydrogen, methane, and other potential food for microbial life.

Other Lost Cities in Outer Space

The Lost City is clearly unlike any other known on Earth, but it’s likely that similar hydrothermal systems exist on other planetary bodies. One example close to home is Jupiter’s moon Europa. If we want to find life in outer space, we must first define the limits to life here on Earth. The Lost City makes a great analog for the types of places to look for life beyond Earth.

The Lost City provided us a new venue for life on Earth; one that does not require energy from the sunlight, or an active planet, but just requires rock plus water. However, many questions about these mysterious serpentinite hosted ecosystems remain unanswered.

In the Deepest Oceans

Early expeditions led by Dr. Deborah Kelly at the University of Washington built a knowledge base for the Lost City. This work led to the discovery that the chimneys undergo chemical, geological, and biological shifts, cool down in temperature and become a more neutral pH as they age.

By sequencing the gene microbiologists use as a barcode, 16S rRNA, they were able to identify the names of the microorganisms that live in the biofilms. Through a combination of sequencing and microscopy, scientists cataloged the microbes living on the chimneys and observed microbes living inside the chimneys are less diverse than those living outside the chimneys. In fact, the more extreme environment of the chimney interiors is dominated by a single species that grows by turning carbon dioxide into methane. This species is named the Lost City Methanosarcinales because it was first characterized in this ecosystem.

From these early expeditions, geochemists realized that the high pH of the system leads the carbon dioxide in the venting fluids to react with the calcium in the seawater, removing it from the fluids and creating an interesting conundrum for the microorganisms. Most ecosystems rely on carbon dioxide as the carbon source at the base of the food web; however, there is no measurable amount of carbon dioxide at the Lost City. A new hypothesis was made that microbes in this ecosystem are instead reliant on formate, a molecule that is basically carbon dioxide with an added hydrogen atom.

DNA Collected From the Lost City

This hypothesis is what drives my own work as an environmental microbiologist in the laboratory of Dr. William Brazelton. I work with DNA sequences collected from the chimney rocks at the Lost City. This DNA holds the answer to how the Lost City microbes can potentially use carbon, but sorting through it is a bit of a computational nightmare. The DNA we get from the chimneys comes from all the cells living on the rock, the seawater, the lab air, even cells of our own skin that slough off as we process the sample in the lab.

To answer our questions, we need to isolate DNA from just a few cells living on the rock. Imagine you had hundreds or thousands of puzzles dumped out onto the floor and were trying to isolate just one of those puzzles to form a picture. I use that pile of puzzles and a very fast computer to try and form a picture of which cells are using formate at the Lost City.

Video recorded by ROV Jason and the Scientific Party of the Return to Lost City 2018 Expedition, Chief Scientist Susan Lang. © WHOI. lostcity.biology.utah.edu

New Insight from Underwater Fluids

In September 2018, I got the chance to see the Lost City in real-time from the perspective of a remotely operated submarine (ROV Jason). The expedition, led by chief scientist Dr. Susan Lang at the University of South Carolina, focused on the venting fluids rather than the chimney rocks. The fluids represent a window into the subsurface where the rock-water reaction that drives the whole vent field takes place.

In order to understand the more complex nuances about this ecosystem, these venting fluid samples were needed. A sampler nicknamed the HOG was specifically designed and built by Dr. Lang to collect the fluids emitting from these chimneys for the first time. 182 water and chimney samples were collected and are currently being analyzed by a collaborative team of researchers from around the world.

This work is made possible by funding from the National Science Foundation and the NASA Astrobiology Institute. To learn more please visit https://lostcity.biology.utah.edu/.

Images Credit: Susan Lang, U. of S.C. / NSF / ROV Jason / 2018 © WHOI