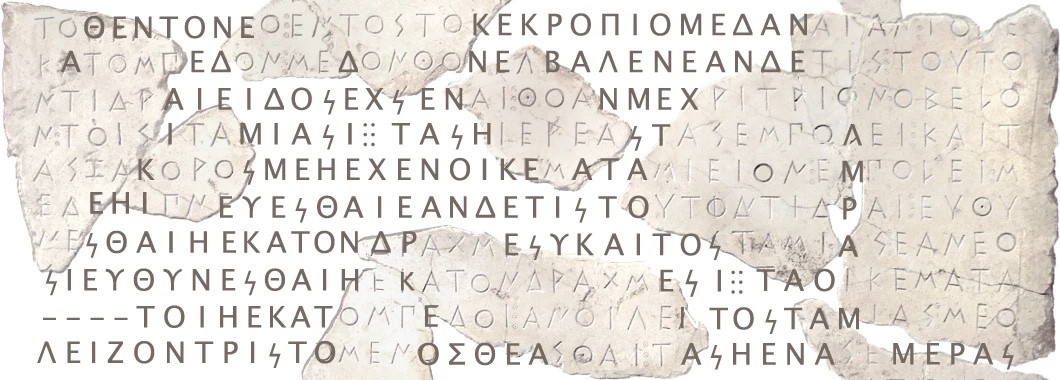

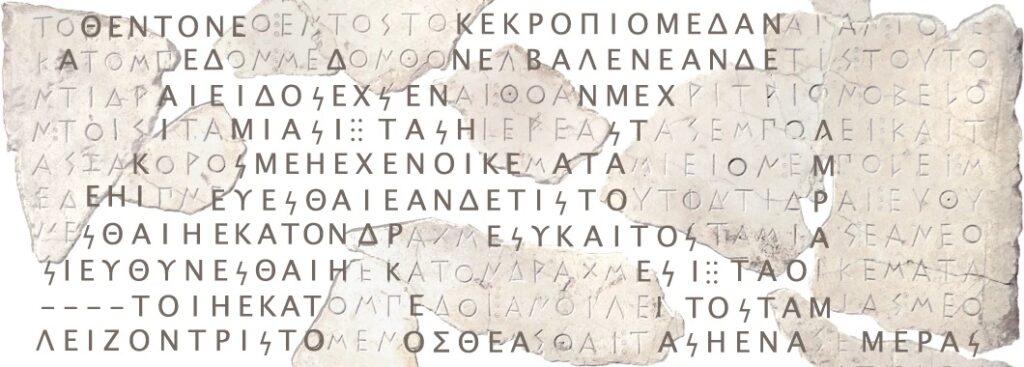

A collaborative study reported in Nature this week (open access) developed Ithaca, a deep neural network architecture that can help historians interpret ancient Greek inscriptions. These inscriptions were written on durable materials such as stones, pottery, and metal found across the ancient Mediterranean world between the seventh century BC and the fifth century AD.

Even though thousands of such artifacts have survived to our time, many are damaged and their texts are fragmentary. Moreover, many of those texts have been moved or trafficked far from their original location.

Epigraphers are specialists in the study of these materials. They reconstruct the missing text, a process known as text restoration, and establish the geographical and chronological attribution (the original place and date of the writing, respectively).

Until now, they have not been able to rely on any known technology, since radiocarbon dating, the method for determining the age of objects, is not useful for inorganic materials.

In this context, Ithaca aims to maximize the collaboration between epigraphers and experts on artificial intelligence to get a better understanding of the inscriptions and make the work of the former a lot easier. Furthermore, Ithaca has an open-source interface, to facilitate its use by historians and the development of further applications.

“The expert historians we worked with achieved 25% accuracy when working alone to restore ancient texts. But, when using Ithaca, their performance increases to 72%, surpassing the model’s individual performance and showing the potential for human-machine cooperation,” pointed out DeepMind, the lead institution undertaking the research.

How does it work

Researchers trained Ithaca with the unprocessed Packard Humanities Institute (PHI), the largest digital dataset of Greek inscriptions. It consists of the transcribed texts of 178,551 inscriptions. After filtering the data, the resulting dataset I.PHI contained 78,608 inscriptions. According to the team, this is the largest multitask dataset of machine-actionable epigraphical text.

Ithaca was trained on inscriptions written in the ancient Greek language because of two main reasons: the variability of contents and context of the Greek epigraphic record, which makes it an excellent challenge for language processing, and the availability of digitized corpora for ancient Greek, an essential resource for training the machine learning model.

This deep learning machine gives inputs to historians to develop the three tasks they do when studying ancient texts: find missing characters and give them geographical and chronological attribution.

For restoration, Ithaca offers a set of the top 20 decoded predictions ranked by probability. This first visualization facilitates the pairing of Ithaca’s suggestions with historians’ contextual knowledge, assisting human decision-making.

For the geographical attribution task, Ithaca classifies the input text among 84 regions, representing its level of certainty. The results are shown on a map to make underlying geographical connections across the ancient world easier.

Finally, to determine the date of the writing, Ithaca produces a distribution of predicted dates across all decades from 800 BCE to 800 CE.

“While Ithaca alone achieves 62% accuracy when restoring damaged texts, the use of Ithaca by historians improved their accuracy from 25% to 72%, confirming the synergistic effect of this research tool. Ithaca can attribute inscriptions to their original location with an accuracy of 71% and can date them to within less than 30 years of their ground-truth ranges, relating key texts of Classical Athens and contributing to topical debates in ancient,” states the research that included DeepMind from London, the Department of Humanities of Ca’ Foscari University of Venice, the Classics Faculty of the University of Oxford, and the Department of Informatics of the Athens University of Economics and Business.

Researchers believe that this tool will help achieve a more holistic understanding of the distribution and nature of epigraphic habits across the ancient world and even contribute to settling current methodological debates in ancient history.

Reference

Assael, Y., Sommerschield, T., Shillingford, B., Bordbar, M., Pavlopoulos, J., Chatzipanagiotou, M., Androutsopoulos, I., Prag, J., & de Freitas, N. (2022). Restoring and attributing ancient texts using deep neural networks. Nature, 603(7900), 280–283. https://doi.org/10.1038/s41586-022-04448-z