In the early 70s, scientists started to figure out the relationship between the ozone layer and the increase in the solar radiation to reach the Earth’s surface. Skin cancer and cataracts were known to be consequences of this increase of ultraviolet radiation.

Scientists were especially concerned with the impact of human activities on the depletion of the ozone layer, an atmospheric layer that protects the Earth from the Sun’s radiation. The mechanisms by which anthropological endeavors impact the ozone layer were not yet clear at that time, but world leaders decided to take action.

A structural framework to the Montreal Protocol

In 1984, several countries signed the Vienna Convention, which provided the support for the notoriously successful Montreal Protocol. In Vienna, the convention signatories agreed to promote cooperation, exchange scientific information of the effects of human activities and to adopt legislative measures against human enterprises likely to have adverse effects on the ozone layer.

The Handbook of the Vienna Convention pointed out several aspects that should be extensively investigated, such as the biological and climatic effects deriving from modifications on the ozone layer and the alternative substances that could replace the ones that might affect the composition and vertical distribution of atmospheric ozone. Halogenated alkanes, most notably known as CFCs, carbon monoxide and carbon dioxide were listed as some of the potential substances that modify the ozone layer.

Putting 197 nations on the same page

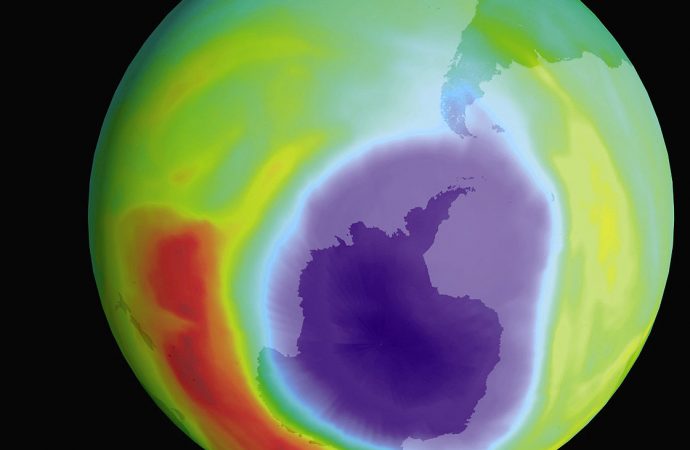

By the end of 1985, 28 nations had signed the Convention. In that same year, researchers had found, over Antarctica, a large and still growing gap in the ozone layer. Investigations intensified and, by the time the Montreal Protocol was set in place, in 1989, the CFCs had already been identified as the major responsible for the modification in the ozone layer.

In the face of the first atmospheric crisis worldwide, the Montreal Protocol urged for a drastic reduction, and eventually elimination, of CFCs’ production. For the first time ever, all the 197 UN members were on the same page: it was urgent to take measures and sign the treaty.

Both the Vienna Convention and the Montreal Protocol are seen as a model of successful negotiations. The former general secretary of UN, Ban Ki-moon, stated the Montreal Protocol is an inspiration and that he “hoped to ensure that we protect our climate the way we have preserved the ozone layer”.

It seems that there are in fact reasons to be optimistic. According to the last UN report on the ozone layer, the ozone layer is “on track to recover by the middle of the century”. Between 2045 and 2060, the ozone layer is expected to return to 1980 levels. However, the UN Report also warns that there are still challenges to overcome and the recovery of ozone levels is going to depend on the concentrations of CO2, methane and nitrous oxide.

How, then, can climate negotiations follow the same fruitful path as the Vienna Convention and Montreal Protocol? Well, we can focus on the reasons why the Montreal Protocol was perhaps the most successful agreement until now.

A simple guide to elaborate a successful agreement

The Montreal Protocol was largely revised and subjected to several amendments and adjustments. This allowed the members to adapt quickly to new scientific data. In fact, the signatories showed an unprecedented foresight, by signing a precautionary document when the scientific mechanisms behind the destruction of the ozone layer were not yet clear.

It was also crucial that various parts of the society were actively involved in the topic. Scientists were involved in the negotiations. Along with several NGOs, they provided a neutral part in the discussions between nations. Chemical industries made an effort to create new products that had little detrimental effects on the ozone layer. On top of that, the public showed an interest in the subject, thanks to a balanced media coverage, and started changing their habits, avoiding the consumption of products that produced CFCs.

In brief, it is no overstatement to say that, on the 22nd of March 1985, the history of mankind took a U-turn. With the Vienna Convention, first, and the Montreal Protocol, subsequently, nations showed that, with a genuine exchange of scientific data and a bit of willingness, it is possible to protect the environment. Hopefully, humanity won’t walk backward and fall victim of false facts.

References:

UNEP – Handbook for the Vienna Convention

UNEP – Handbook for the Montreal Protocol

The New Yorker – The Weight of the World

UN Reports – Scientific Assessment of Ozone Depletion 2014