The study of ancient ships can uncover great knowledge about past and future civilizations. The ShipLAB wants to make it a worldwide collaborative effort.

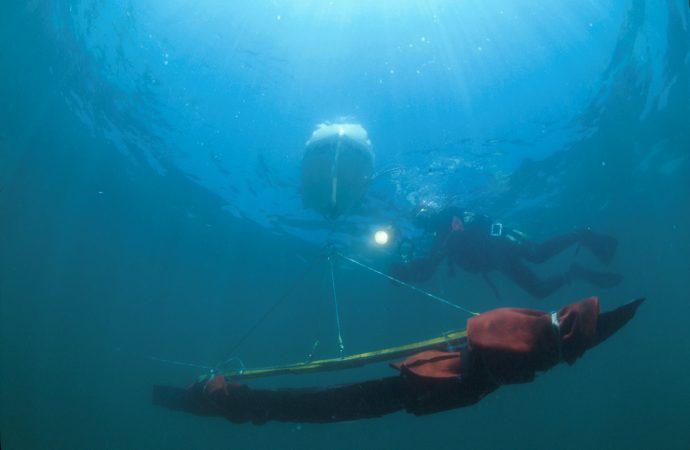

Computers are changing archaeology as much as they are changing the world. Maritime archaeologists welcome these developments, perhaps mostly in the subfield of nautical archaeology, which studies the history of watercraft. Computers are making the traditionally expensive and complex tasks of surveying, identifying, inspecting, assessing, recording and reconstructing shipwrecks cheaper, easier, quicker, and more accurate.

Nautical archaeology took its first steps as an academic discipline around 1960, the year George Bass started the underwater excavation of a Bronze Age shipwreck at Cape Gelidonya, in Turkey (Bass 1961). The following year a group of Swedish institutions raised the 17th century warship Vasa, and in 1962 Danish archaeologist Ole Crumlin Pedersen excavated five Viking ships sunk in the 11th century at Skuldelev, Denmark. Over the following decades nautical archaeology became a mainstream subfield of archaeology and, in 1976, Texas A&M University invited George Bass, Frederick van Doorninck and J. Richard Steffy to settle in Texas, create the Nautical Archaeology Program and base the Institute of Nautical Archaeology.

The ShipLAB

The Ship Reconstruction Laboratory (ShipLAB) was created by J. Richard Steffy that same year and has been a center for teaching, researching, and disseminating knowledge related to the history of ships around the world. Today it is one of the laboratories of the Centre for Maritime Archaeology and Conservation, and part of the Anthropology Department at Texas A&M University.

Dedicated to the study of the history of watercraft, the ShipLAB is engaged in several partnerships to research a wide array of problems, at Texas A&M University with the Evans Library, the Department of Computer Science / Center for the Study of Digital Libraries, as well as the Department of Visualization.

In Europe the ShipLAB is part of a number of projects, such as Groplan, ForSEAdiscovery, or iMARECULURE, involving the Centre National de la Recherche Scientifique / Laboratoire des Sciences de l’Information et des Systèmes, the Universidade Nova de Lisboa / Instituto de Arqueologia e Paleociências/ Centro de História Contemporânea, the Centro de Ciencias Humanas y Sociales, or the Cyprus University of Technology.

The social value of archaeology

The ShipLAB is also interested in promoting a reflection on the social value of archaeology in the beginning of the XXI century, at a time when western governments are increasingly engaged in across the board budget cuts and diminishing public responsibilities, privatizing their traditional functions and abandoning the environment and the cultural resources to the forces of the markets.

Working for both public and private institutions, archaeologists constantly construct and deconstruct narratives about our past, but traditionally publish only a fraction of the sites they excavate and thus destroy. Computers and the internet present a vast range of opportunities for archaeologists to share primary data and foster intercultural online collaborations and reinterpretations of archaeological contexts. As about 50% of the world population is gaining access to the internet, and over 90% of the planet’s younger population are literate, the XXI century appears as an unprecedented age where narratives will multiply, together with interested publics and stakeholders.

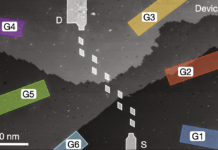

At Texas A&M University, students are researching the possibility of using off-the-shelf software packages such as PhotoScan, Rhinoceros, Maya, or Houdini to map, represent, and reconstruct shipwrecks. Web-based platforms such as Sketchfab, Academia, ResearchGate, or even Facebook are offering amazing opportunities for data sharing and the creation of fora where archaeological projects can be discussed and cooperation projects initiated.

Collaboration supplants competition

It seems that the old competitive paradigm, with isolated scholars working in isolation, and keeping their primary data close to their chests is being replaced by a multi-cultural, far more fluid environment where communities – the opposite of competitive environments – are formed and international cooperation is the rule. The ShipLAB wants to be a vigorous proponent of this change and help universities and research institutions understand that the traditional metrics, such as citations, peer review gatekeeping systems, rankings, and other measures of popularity will have to be reviewed sometime soon.

Although computing power is growing at a slower pace than the universe of possibilities envisioned by computer scientists, as costs drop and technology becomes increasingly available, even against a background of growing social injustice and inequality, computers are undoubtedly creating opportunities to make archaeology and its narratives about our past more democratic, less elitist, and more prone to serve as a provider of thinking tools and learning environments that may help the inhabitants of our flat world – soon to be 10 billion – to understand the present and imagine spaces of utopia. As Foucault wrote, “after all, the ship is at the same time the biggest instrument of economic development, and the largest reserve of imagination. The ship is the ultimate location of utopia. In civilizations without ships dreams dry out, espionage replaces adventure, and the police, the pirates” (1967).

References:

Bass, G. (1961). The Cape Gelidonya Wreck: Preliminary Report American Journal of Archaeology, 65 (3) DOI: 10.2307/501687

Foucault, M., 1967, “Des espaces autres,” in Architecture, Mouvement, Continuité, n°5, octobre 1984, pp. 46-49.

Images Credits: Heritage Auctions / Wikimedia Commons; Gui Garcia; Audrey Wells